Saint Anthony of Padua

Confessor, Doctor of the Church

1231

Although he was a native of Lisbon, Anthony derived his

surname from the Italian city of Padua, where his mature years were passed

and where his relics are still venerated in the basilica, Il Santo. He was

born in 1195 of a noble Portuguese family, and was baptized Ferdinand. His

parents sent him to be educated by the clergy of the cathedral of Lisbon.

At the age of fifteen he joined the canons regular of St. Augustine, and

at seventeen, in order to have more seclusion, asked for and obtained

leave to transfer to the priory of St. Cross, of the same order, at

Coimbra, then the capital of Portugal. There, for a period of eight years,

he devoted himself to study and prayer. With the help of a remarkable

memory he acquired a thorough knowledge of the Scripture.

In the year 1220, Don Pedro, crown prince of Portugal,

brought back from Morocco the relics of some Franciscan missionaries who

had recently suffered martyrdom. The young student conceived an ardent

desire to die for his faith, a hope he had little chance of realizing

while he lived in a monastic enclosure. He spoke of this to some mendicant

Franciscans who came to St. Cross, and was encouraged by them to apply for

admission to their order. Although he met with some obstacles, he at

length obtained his release and received the Franciscan habit in the

chapel of St. Anthony of Olivares, near Coimbra, early in 1221. He changed

his name to Anthony in honor of St. Anthony of Egypt, to whom this chapel

was dedicated.

Almost

at once he was permitted to embark for Morocco on a mission to preach

Christianity to the Moors. He had scarcely arrived when he was prostrated

by a severe illness, which obliged him to return to Europe. The ship in

which he sailed for home was driven out of its course by contrary winds

and he found himself landed at Messina, Sicily. From there he made his way

to Assisi, where, he had learned from his Sicilian brethren, a chapter

general was about to be held. It was the great gathering of 1221, the last

chapter, as it proved, open to all members of the order, and presided over

by Brother Elias, the new vicar-general, with the saintly Francis seated

at his feet. The whole spectacle seems to have deeply impressed the young

Portuguese friar. Almost

at once he was permitted to embark for Morocco on a mission to preach

Christianity to the Moors. He had scarcely arrived when he was prostrated

by a severe illness, which obliged him to return to Europe. The ship in

which he sailed for home was driven out of its course by contrary winds

and he found himself landed at Messina, Sicily. From there he made his way

to Assisi, where, he had learned from his Sicilian brethren, a chapter

general was about to be held. It was the great gathering of 1221, the last

chapter, as it proved, open to all members of the order, and presided over

by Brother Elias, the new vicar-general, with the saintly Francis seated

at his feet. The whole spectacle seems to have deeply impressed the young

Portuguese friar.

At the close of the proceedings the friars set out for

the posts assigned to them by their respective provincial ministers. In

the absence of any Portuguese provincial, Anthony was allowed to attach

himself to Brother Gratian, the provincial of Romagna, who sent him to the

lonely hermitage of San Paolo, near Forli, either at his own request, that

he might live for a time in retirement, or as chaplain to the lay friars

of the community. We do not know whether Anthony was already a priest at

the time. What is certain is that no one then suspected the brilliant

intellectual gifts latent in the sickly young brother. When he was not

praying in the chapel or in a little grotto, he was serving the other

friars by washing their cooking pots and dishes after the common meal.

His talents were not to remain hidden long. It happened

that an ordination service of both Franciscans and Dominicans was to be

held at Forli, on which occasion all the candidates for consecration were

to be entertained at the Franciscan Convent there. Through some

misunderstanding, not one of the Dominicans had come prepared to deliver

the expected address at the ceremony and no one among the Franciscans

seemed ready to fill the breach. Anthony, who was present, perhaps in

attendance on his superior, was told by him to go forward and speak

whatever the Holy Ghost put into his mouth. Diffidently, he obeyed. Once

having begun he delivered an address which astonished all who heard it by

its eloquence, fervor, and learning. Brother Gratian promptly sent the

brilliant young friar out to preach in the cities of the province. As a

preacher Anthony was an immediate success. He proved particularly

effective in converting heretics, of whom there were many in northern

Italy. They were often men of education and open to conviction by Anthony’s

keen and resourceful methods of argument.

In addition to his work as an itinerant preacher, he

was appointed reader in theology to the Franciscans, the first to fill

such a post. In a letter, generally considered authentic, and

characteristically guarded in its approval of book learning, Francis

himself confirmed the appointment. "To my dearest brother Anthony,

brother Francis sends greetings in Jesus Christ. I am well pleased that

you should read sacred theology to the friars, provided that such study

does not quench the spirit of holy prayer and devotion according to our

rule."

Anthony spent two years in northern Italy, after which

he taught theology in the universities of Montpellier and Toulouse and

held the offices of guardian or prior of a monastery at Puy and of

custodian at Limoges. For his ability in formulating arguments against the

heresies of the Albigensians, he became widely known under the sobriquet

of "Hammer of Heretics." It became more and more plain that his

career lay in the pulpit. Anthony had not Francis’ sweetness and

simplicity, and he was no poet, but he had learning,, eloquence, marked

powers of logical analysis and reasoning, a burning zeal for souls, a

magnetic personality, and a sonorous voice that carried far. The mere

sight of him sometimes brought sinners to their knees, for he appeared to

radiate spiritual force. Crowds flocked to hear him, and hardened

criminals, careless Catholics, heretics, all alike were converted and

brought to Confession. Men locked up their shops and offices to go and

attend his sermons; women rose early or stayed overnight in church to

secure their places. When churches could not hold the congregations, he

preached to them in public squares and market places.

In 1226, shortly after the death of St. Francis,

Anthony was recalled to Italy, apparently to become a provincial minister.

It is not clear what his attitude was towards the dissensions which were

rising everywhere in the order over the nature of the obedience to be paid

to the rule and testament of Francis. Anthony, it seems, acted as envoy

from the discordant chapter general of 1226 to the innovating Pope Gregory

IX, to lay before him the various conflicts that had arisen. On that same

occasion he obtained from Gregory his release from office-holding, so that

he might devote himself to preaching. The Pope had a high respect for him,

and because of his extraordinary familiarity with the Scriptures once

called him "the Ark of the Testament."

Thereafter Anthony made his home in Padua, a city which

he already knew and where he was highly revered. There, more than anywhere

else, he could see the results of his ministry. Not only were his sermons

listened to by enormous congregations, but they led to a widespread

reformation of morals and conduct in the city. Long standing quarrels were

amicably settled, hopeless prisoners were liberated, owners of ill-gotten

goods made restitution, often in public at Anthony’s feet. In the name

of the poor he denounced the prevailing vice of extortionate usury and

induced the city magistrates to pass a law exempting from prison debtors

willing to surrender all their possessions to satisfy their creditors. He

is said to have ventured boldly into the presence of the truculent and

dangerous Duke Eccelino II, the Emperor’s son-in-law, to plead for the

liberations of some citizens of Verona whom the duke was holding captive.

The attempt was unsuccessful, but due to the respect he inspired he was

listened to with tolerance and allowed to depart unmolested.

In the spring of 1231, after preaching a powerful

course of sermons, Anthony’s strength gave out and he retired with two

of the brothers to a woodland retreat. It was soon clear that his days

were numbered, and he asked to be taken back to Padua. He never got beyond

the outskirts of the city. On June 13, in the apartment reserved for the

chaplain of the sisterhood of Poor Clares of Arcella, he received the last

rites and died. He was only in his thirty-sixth year. Within a year of his

death he was canonized, and the Paduans have always regarded his relics as

their most precious possession. They built a basilica to their saint in

1263.

The innumerable benefits he has won for those who

prayed at his altars have obtained for Anthony the name of the

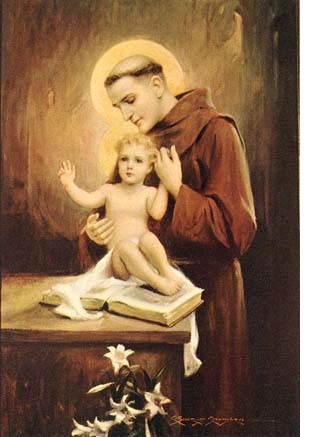

"Wonder-working Saint." Since the seventeenth century he was

often been painted with the Infant Savior on his arm because of a late

legend to the effect that once, when stopping with a friend, his host,

glancing through a window, had a glimpse of him gazing with rapture on the

Holy Child, whom he was holding in his arms. In the earlier portraits he

usually carries a book, symbolic of his knowledge of the Bible, or a lily.

Occasionally he is accompanied by a mule which, legend says, fell on its

knees before the Sacrament when upheld in the hands of the saint, and by

so doing converted its heretical owner to a belief in the Real Presence.

Anthony is the special patron of barren and pregnant women, of the poor,

and of travelers; alms given to obtain his intercession are called

"St. Anthony’s Bread." How he came to be invoked, as he now

is, as the finder of lost articles has not been satisfactorily explained.

The only story that bears on the subject at all is contained in the

so-called Chronicles of the Twenty-four Generals, number 21. A

novice ran away from his monastery carrying with him a valuable psalter

which Anthony had been using. He prayed for its recovery and the novice

was frightened by a starling apparition into bringing it back.

A Sermon by Saint Anthony of Padua

First Sunday after Pentecost

Love

"God is love," we read today at the beginning

of the Epistle. (I John iv, 8) As love is the chief of all the virtues, we

shall treat of it here at some length in a special way . . . .

If God loved us to the point that he gave us his

well-beloved Son, by whom he made all things, we too should ourselves love

one another. "I give you," he says, "a new commandment,

that ye love one another (John xiii, 34)." . . . We have, says St.

Augustine, four objects to love. The first is above us: it is God. The

second is ourselves. The third is round about us: it is our neighbor. The

fourth is beneath us: it is our body. The rich man loved his body first

and above everything. Of God, of his neighbor, of his soul, he had not a

thought; that was why he was damned.

Our Body, says St. Bernard, should be to us like a sick

person entrusted to our care. We must refuse it many of the worthless

things it wants; on the other hand, we must forcefully compel it to take

the helpful remedies repugnant to it. We should treat it not as something

belonging to us but as belonging to Him who bought it at so higha price,

and whom we must glorify in our body (I Corinthians vi, 20). We should

love our body in the fourth and last place, not as the goal of our life

but as an indispensable instrument of it.

(Les Sermons de St. Antoine de

Padoue pour L’année Liturgique. Translated by Abbe Paul Bayart,

Paris, n.d.)

— From Lives of Saints,

John J. Crawley & Co., 1954

|